Legendary Eathorne Touched Countless Lives

By Terry Mosher

Posted: July 06, 2010 – Kitsap Sun

An important part of Bremerton’s sports history died Monday when Les Eathorne succumbed to congestive heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease at the age of 86. There may never be another like him.

Eathorne graduated from Bremerton High School in 1942, when the city was booming and the shipyard was busy with World War II.

Those years became a golden age of athletics in Bremerton. Eathorne became one of the “Golden Boys” along with athletes such as Roger Wiley, Ted Tappe, Louis Soriano, Don Heinrich and many others.

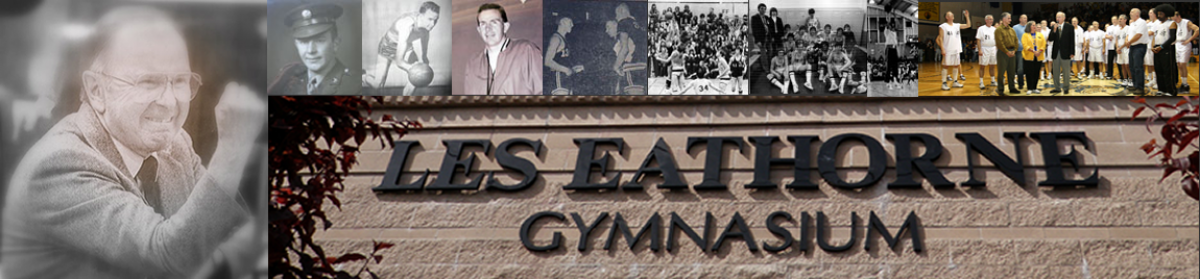

Legendary coach Ken Wills was the conductor for Bremerton basketball. His name became attached to the Bremerton gymnasium floor last December, at the same time the gym was named for Eathorne.

Eathorne played for Wills in 1941, when the Wiley-led Wildcats won the state basketball tournament. The following season, Eathorne’s senior year, the Wildcats lost the state title game by two points to Hoquiam.

Wiley wound up at the University of Oregon and Eathorne might have gone there, too, if it wasn’t for the in-home conversation Eathorne’s mother had one day with renowned University of Washington basketball coach Hec Edmundson.

Edmundson came across so well that Eathorne’s mother was determined her son would go to Washington. And whatever was good enough for his mother was good enough for him. So off he went to Washington for a college basketball career that was interrupted by the war and his military service. He was slowed upon his return by a heart condition.

Eathorne would come back to Washington after his military service and play basketball despite his heart condition.

Later he become a high school basketball coach whose career surpassed his mentor, Wills.

Eathorne’s coaching career included seven seasons at Camas (1949-’56), 22 at East Bremerton (1956-’78), 10 at Bremerton High (1978-’88) and two more at Olympic High (1995-’97). By the time he retired he had collected 502 wins and two state championships (1973 and ‘74).

He was inducted into the Washington State Basketball Coaches Association Hall of Fame in 1993 and 12 years later earned a spot in the Kitsap County Sports Hall of Fame. Eathorne was most proud of being named the National High School Athletic Director of the Year in 1975.

There is little debate that Eathorne had a lasting impact on players, coaches and officials in the area.

Bruce Enns of Bremerton did most of his coaching on the college level in Canada and continues to coach on the international level.

“He really cared about kids,” said Enns, who grew closer to Eathorne in recent years. “That’s the big thing.”

Referee Charlie Buell is proud that he never called a technical foul on Eathorne, an intense coach who would often question calls.

But maybe the best memory Buell has of Eathorne is being taken care of by him. Eathorne and Buell’s mother went to school together at Bremerton.

“They were good friends and I remember when I was either in the seventh or eighth grade, she took me down to the gym and he put me in the whirlpool,” Buell said. “I had pulled a muscle and I remember thinking that thing was going to kill me.”

But Buell got better. That was Eathorne. Always sure to take care of kids.

Like Wills, Eathorne opened the gym on Sundays and kids like Buell would show up. It was a way to attract kids to his program. He even encouraged players from other schools to attend, especially from South Kitsap. It was a bigger school and Eathorne hoped playing against those kids would improve his.

That’s also why he encouraged college players to attend open gyms. He would separate games by the quality of talent. The best players would be at one end.

Eathorne also thought it was important to show the kids that he knew the game and could play it, so he joined in during the early years. It was all about gaining confidence, respect and trust in the players he coached.

Rick Walker became All-American while leading East Bremerton to consecutive state titles in 1973 and ‘74. But as a sophomore, he was uncertain as one could get about his status with coach.

“I was scared of him,” Walker said. “He made the freshmen fear and tremble before him. He was always probably a lot easier with the upperclassmen, especially the seniors. But he sure was tough on me.”

Eathorne only occasionally told Walker “good job” or gave him a wink of acknowledgment that he was doing the right thing.

“I wasn’t sure if I was going to make the team, even as a junior,” Walker said. “He always wanted you to work as hard as you could to impress him. Even then I really didn’t know what he was thinking. It was his way of keeping everyone humble.”

One time Walker said he was injured and tried to play through it because he wasn’t sure where he stood. Eathorne finally came over to him and told him he didn’t have to run with the rest of the players.

“I mentioned something about wanting to make the team and he said something like, ‘You don’t have to worry about it,’” Walker said. “The one thing that impressed me was after tryouts he would get everybody together and tell everybody involved why he wasn’t going to make the team, and what it was he needed to work on. It was all good information for you to know rather than just being a name on a sheet of paper taped to a window. He didn’t ridicule anybody in the process. He would tell them what they needed to work on and for them to come back next year and prove him wrong.”

Back in the heyday of East High, when the Knights won consecutive state championships, the gym would be full before the junior varsity game finished.

The excitement and the tension that filled the gym could be felt. The lights would go out during player introductions and a searchlight would flash around the gym, the band would play, the cheerleaders would cheer, and the world of high school basketball never seemed bigger.

And a big part of that was the old East High Dad’s Club that sat in the southwest bleachers and roared approval as loud, if not louder, than the rest.

“It was a big thing,” said Dave Hayford, whose son played for Eathorne. “We had a heck of a lot of fun in the old gym. It was just a wonderful experience for my wife and me and for a ton of other friends.”

The club would get together for postgame parties at members’ homes. Eathorne, of course, would be the main course.

“Les was just one heck of a good guy to be around,” Hayford said. “He stuck up for his kids. By God, he fought for them. He loved his kids and backed them to the hilt.”

Jim Rye played for him — sparingly because of a knee injury his senior year — and later officiated basketball games. Rye had a reputation for being quick about teeing up coaches who got a little out of line, and Eathorne was not an exception.

“He was a great guy,” Rye said. “If he did get a technical there was a reason for it. Lots of times he knew he could spur his team on. So he would get one (a technical) and then leave you alone. He ‘played’ the officials. He was good at it.”

Rye is among the many former players who gush when they explain how much Eathorne meant to them as they have moved on with their lives.

“That’s because he really cared about you,” Rye said. “Most coaches just care about winning and losing, but he would make sure you were doing your studies, and he cared about his players building good character. He tried to bring the best out of everybody. Yes, he was a great coach, but you got so much more respect for him because he would take the time to ask how you were doing. And he sincerely cared.

“I think he cared about you more as a person (than a basketball player). He wanted all his players to succeed in whatever direction they were going.”

Before full-court pressure became common in basketball, Eathorne developed that style back in the 1950s when one of his former players, Lyle Bakken, became a one-man defensive wrecking ball. It worked so well, Eathorne started the zone full-court pressure for which his teams became famous.

“I remember running the lines in practice,” Rye said. “We would be just about dead and he would want us doing it a couple more times. He wouldn’t do it out of meanness. He did it because he knew you could do it, and that is how East High ran teams on the floor. It was his style and he wanted us to believe in his style. You don’t stop. You just kept going.

“He was kind of the John Wooden of high school basketball.”

Former North Kitsap coach Jim Harney worked hard to match what Eathorne had built at East. The result was a fierce rivalry that played out in the local paper and caused some friction between the two. But in retirement, the two became fast friends. The would often meet in Silverdale for breakfast.

“He was unbelievably entertaining,” Harney said. “It’s his wit. He was very quick and very spontaneous. Really, I would just crack up.”

Kids growing up in East Bremerton couldn’t wait to play for Eathorne. Wayne Gibson graduated in 1964 from East, but he said he dreamed years before that about playing for Eathorne.

“He had such a good program back then that playing on the varsity was a big deal,” Gibson said. “He gave me a lot of confidence that I could do anything I wanted to do. He gave me a lot of self-confidence, and what better compliment can you give a coach then that?”

Bruce Welling, who just finished up his 39th year of teaching at Central Kitsap, played for Eathorne in the 1960s and if Eathorne asked him today to do something, he would snap to it.

“If he would have asked me to run through the wall into the auxiliary gym, I would have done it,” Welling said. “You had that much respect and trust in the man that you would follow through. He treated you as a human being. He respected us and our abilities and when somebody respects you, you respect him back, you believe in him.

“… I was a basketball player for him, but I was human being for him, too. I was an individual. I was somebody important. That’s the way he made everybody feel.”

Coaches like Eathorne are rare. They don’t come along often. His name, his memory will last long after he is gone. But that’s not all he was.

“He was a great coach,” Louie Soriano said. “But the thing you are forgetting is he was a great basketball player. He really was. Many of the kids growing up then were always trying to emulate the things he did. He could pass, could dribble, was a smart player and could shoot really well. He was at the time the greatest basketball player locally we had an opportunity to see.

“That was a great era back then and the young kids looked up to heroes like him.”

Eathorne’s sister, Virginia Costello, said from her home in Bremerton, “I am heartbroken. But he lived a good life. He worked hard for kids and people and I’m very proud of him.

“I’m very proud to be his sister.”