West Sound Athletes of the Century: Coach Ken Wills

By John Wallingford, Sun Staff

Captain Bob “Inky” Engstrom, left, and coach Ken Wills, third from left, accept trophies after Bremerton won the 1941 state basketball championship. The Wildcats edged St. John 30-29 in the title game. Wills compiled a 472-184 record from 1936-62 and took the Wildcats to 15 state tournaments, winning one and placing second three times.Wills won Pacific Coast Conference All-Northern Division honors in basketball at Washington State and narrowly missed out on a bid to make the 1932 U.S. Olympic team as a miler.

” Bremerton coach Wills pushed kids to work hard, play defense beeline to UW with hard work, defense .”

The record says that on a tragic day 37 years ago, ken wills died from a self-inflicted bullet wound.

For the legion of players whose lives he transformed, the mark their mentor, friend and colleague left on them is imperishable.

Wills, The Sun’s coach of the century, was surrogate father to a generation of Bremerton boys who played basketball and ran track under his guidance.

“”We were a damn fortunate bunch of guys,”” said Louie Soriano, a two-time all-state basketball player under wills whose blue eyes tend to water when the subject turns to his beloved mentor. “”I don’t think any one of us, including Ted Tappe, who was so talented, would’ve achieved anything if it hadn’t been for ken wills.””

And this is no mere clinging-to-the-glory-days sentiment kind of story.

It is true that wills, an elite miler and former major-college basketball player who coached hoops and track in Bremerton from 1936-62, could have won the honor on empirical data alone. In 26 years as hoops coach at Bremerton and then West Bremerton high schools, wills won 72 percent of his games. He compiled a 472-184 record and took the Wildcats to 15 state tournaments, winning one and placing second three times.

But this isn’t about the spoils of victory.

And yes, his passion for perfection and a martinet’s will in teaching fundamentals, particularly when it came to man-to-man defense, and his ethos of mind-bending work prepared a singular stream of players for success in major-college basketball.

But that’s not the heart of the matter, either.

If you’re unsure why wills was a peerless mentor in the annals of Kitsap sport, allow 1944 Bremerton grad Joe Stottlebower to ram the message home.

“”He cared for a lot of kids who didn’t play basketball,”” said Stottlebower, who made second-team all-state in his senior year, when the Cats took sixth. “”ken wrote long letters to people in uniform (during World War II). He was extremely unselfish.

“”I’ve coached up in Bellingham (as assistant to 1943 alum Boyd McCaslin), and you’re interested in kids who are 7 feet tall and are going to help you. ken was interested in 5 feet tall and aren’t going to help you.””

In the beginning

Wills, who was born in Idaho and picked fruit around Walla Walla as a boy, left Kelso to teach physical education and coach at Bremerton. It was 1936, when center-jumps were still contested after each basket and the press referred to players as “”casaba tossers.””

At 25, wills was an intense man given to swift movements and possessing a boundless reservoir of nervous energy. Just three years removed from earning Pacific Coast Conference All-Northern Division honors in basketball at Washington State and four years from narrowly missing out on a bid to make the 1932 U.S. Olympic team as a miler, he sported an athletic, sinewy physique.

When he got here, he launched an unorthodox ministry of basketball. An avowed agnostic, wills had little faith in organized religion. That, coupled with his practice of opening the school gym for Sunday-afternoon pickup games, ran him afoul of the town’s conventional clergy on occasion.

But he had so much to do, and so little time.

On Dec. 2, 1936, Bremerton’s state-champion football team, about to set sail for Hawaii for a postseason game, received front-page play in the Daily News Searchlight, including a team photo at top-center. On the next day, the Wildcat cagers, preparing for their opener against Port Angeles, got a brief blurb on page four.

“”wills has given most of his attention so far this year to instilling fundamentals into his players,”” it was reported, “”so consequently has developed little in the way of an offense so far.””

Little would change over the next 26 years.

As for wills’ inaugural, Bremerton won 28-15, getting 12 points from future Washington All-American Bill Morris and eight from senior Stewy McIntyre.

“”Bremerton was actually a football school,”” McIntyre said. “”We were still shooting the two-hand shot at that time, and ken taught us the one-hand push shot and how to move the ball to the basket. He played hard, and he taught us to play hard.””

Now 81 and living in Bremerton, McIntyre has vivid memories of his early encounters with wills.

“”The first time I turned out,”” McIntyre said, “”he asked me, ‘Where’d you get those basketball shoes?’ I told him they were my shoes from last year,’ and he said, ‘If you don’t wear out two pairs of shoes for me, you won’t be playing.’ “”

A new era had dawned.

Open gyms and building tradition

Ask any of wills’ players, and they’ll laud his unprecedented open-gym policy. Former players, many playing in college, would return on weekends to mix it up with the younger crowd.

“”He used to run summer basketball programs before other people even thought of it,”” said McCaslin, who played college ball at Michigan and went on to coach preps for 34 years, including a stint at Bellingham from 1952-60.

“”We used to walk over to High Street from Lincoln Junior High so we could look up 11th Street and see the high windows of the old high school and see if the lights were on. If the team was practicing, we would go down there and shoot baskets around the edge.””

“”That gym was a magnet,”” said 1949 grad Wally Erwin. “”He was there all summer long, and there was always a basketball on the floor. He made it available to us, played with us and talked to us.””

The preachers weren’t the only people concerned about the open gyms.

“”I think that was a great irritation to all the other coaches in the area,”” said Darwin Gilchrist, class of ’46 and a standout with the Olympic College team that placed third at the 1949 junior college nationals.

“”They saw that he made the gym open on weekends and in the summer for anybody to come and play around. Other schools, as soon as school was out, they locked everything up. I remember the Poulsbo coach cornered me once and asked me about that.””

McIntyre remembers a stripling boy, maybe 7 or 8 years old, who became a regular rat during turnouts at the gym at the old school on High Street between Fourth and Fifth streets.

By the time the little gym rat, Soriano, reached seventh grade at Lincoln JHS, he had become quite an irritation to opposing players.

He was one of wills’ most devout converts to the church of work, sacrifice and strict observation of fundamentals. Soon he was dribbling a basketball around town and pushing lungs and legs through 20-yard starts to improve his explosiveness.

“”He told me, ‘I want you to dribble up the sidewalk; I want you to dribble out in a field where there are ruts,’ “” Soriano said.

Defense was the chief concern for wills, who developed an aversion to zones long before Bobby Knight let loose his first temper tantrum.

And in the fun-loving days of wooden paddles and corporal punishment, you had better move your feet and keep your hands up.

“”We were assigned to a guy,”” Soriano said, “”and if we didn’t do a good job, we took a hack.””

Now 69, Keith Jefferson moved to Bremerton in 1940, where his dad had worked in the shipyard during World War I. As the war in Europe broadened, opportunities for work in the yard exploded.

Jefferson didn’t take up the game until he was a 13-year-old frosh and received encouragement from wills.

“”He said anybody can be a basketball player,”” Jefferson said.

But he never said it would be easy. Jefferson didn’t dress for a varsity game until he was a senior, when he started for the ’46-47 Cats. Soriano was the only returner from a team that lost the state championship game to Roosevelt. The other starters were Bill Alexander and a pair of juniors and nascent Bremerton legends, Don Heinrich and Tappe.

Being a member of one of wills’ starting five, Jefferson said, was a thrill to remember for a lifetime.

“”He was the guy that you looked up to because of all the famous guys who had gone before you and the reputation of Bremerton basketball,”” said Jefferson, who remembers the trying moments, like the day wills slammed his megaphone down and bellowed, “”You may be a basketball player someday Jefferson, but you’ll probably be 30 years old.””

College-bound Cats

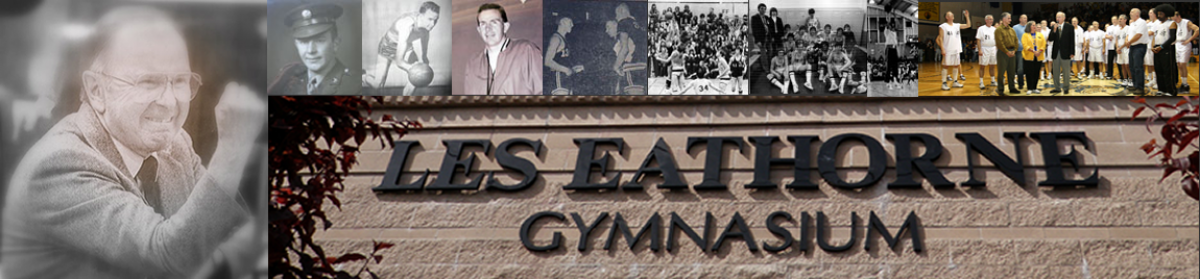

The pipeline wills laid between Bremerton and Montlake became an essential feature of the Cat tradition. By the time Jefferson made varsity, wills had sent Morris, Bob “”Inky”” Engstrom and Les Eathorne to the Huskies.

The time spent laboring in the shadows paid off.

“”When I turned out for freshman ball at the U-dub as a walk-on, I was amazed at how poorly prepared most of these guys who were hotshots over in Seattle were,”” Jefferson said. “”They couldn’t play defense and they didn’t have much of a team concept.””

Jefferson earned a scholarship by his junior year.

And it wasn’t just the UW. In the fall of 1937, McIntyre and Phil Mahan turned out for the frosh team at WSU.

“”We were the only ones who knew how to fake and go around,”” McIntyre said. “”We were so far ahead of the others, it was funny.””

Gilchrist, now 72, landed at Long Island University, partly because he was a nightmare for the guy he was guarding.

“”I played in that independent league in Seattle, and it wasn’t uncommon for people to ask me, ‘How come all those Bremerton players play defense so good?’ “” he said.

Other wills players who played at Washington include Soriano, Charley Koon, Russ Parthemer, Bob Bryan, Ron Patnoe and Al Murphy.

“”If you could play for ken wills, you quite often did not have to be an excellent athlete to be a very, very good ballplayer,”” Eathorne said. “”You can measure him any way you want to, but how many kids got to college mainly because of their athletic ability? And a lot of their parents didn’t have the money to put them through, and they got through college because they played basketball well enough to get financial aid.””

Sid Ryen, Gilchrist’s classmate who starred at the University of Denver and was twice drafted by the NBA, wasn’t enamored with all of wills’ decisions.

“”When I got to college and guys got stymied bringing the ball upcourt, I went up there and dribbled the ball, and it was easy,”” Ryen said. “”He wasn’t easy to play for. He had his favorites. … I was ordered not to shoot. It was not a request.

“”He wasn’t right in everything. I don’t know if he was wrong in that.””

‘Ta’

When wills arrived at Bremerton, Thelma Dane, class of ’29, was working as the secretary to Principal Harry Sorenson. Within three years, the new coach and the Bremerton woman were married.

For the next 23 years, Thelma, or “”Ta,”” as most address her, would be an integral part of the program. Downright vivacious at 88, she remains at their Trenton Avenue house overlooking Rich Passage. She has shouldered forward for 37 years, since the day a despondent wills ended his life and plunged a community into bewildered mourning. At 52, wills was cajoled into taking the OC basketball job, a job many believe he never wanted, in the wake of Phil Pesco’s death. He lasted less than a day.

Ta said wills became infatuated with basketball by junior high, but couldn’t crack the lineup at Walla Walla, the state’s dominant team of that era. So he passed time waiting for the local YMCA to open, likely developing his empathy for aspiring players sitting on the fringes.

“”He just worshiped that basketball,”” Ta said. “”It was a living element to him.

“”To him, everything was in those formative years. He’d see a boy hanging around, and he’d say, ‘I know that kid wouldn’t be in there watching if he didn’t want to be a ballplayer.’ “”

State champs

In 1941, wills took the Cats to Washington’s prep roundball summit.

Their bellwether was all-state senior Allan Maul. The team also included speedy Hal Worland, Engstrom, Eathorne, Ed Devaney, Maurice “”Soupy”” Campbell, Barney Naon, Bill Long, Klem Longley and Mack Adams.

In the title game, the Cats were led by an awkward 6-foot-8 junior. His name is Roger Wiley, and he scored 10 points in a 30-29 win over pesky St. John.

“”ken would be the most influential person in my life,”” said Wiley, now 75 and living in Port Angeles. “”He got me at a time when I needed it. My life today is easily attributable to ken wills. Most of us in Bremerton ended up in apprenticeship in the navy yard. My folks could not support me.””

Much to the chagrin of UW coach Hec Edmundson, Wiley attended the University of Oregon on a scholarship. He scored 1,163 points in a career interrupted by the war, averaged 14.7 points a game as a senior in 1949 and earned Pacific Coast Conference All-Northern Division honors, and got a doctoral degree and ended up as head of the physical education department at WSU.

Eathorne has a scrapbook that chronicles his junior and senior seasons, the latter ending with a 36-34 loss to Hoquiam in the state finals. It features an opening entry dated Dec. 1, 1941: “”Please let me tell you of the man who is most responsible for this book; he is my coach, ken wills. He developed what small natural talent that I had and worked with me for hours that run into days and then months.””

When Eathorne was 7, his father, a machinist, suffered a debilitating brain injury in the yard. wills became a second father to the aspiring shooter.

“”He was a very, very unusual man,”” Eathorne said. “”You just didn’t jump right into this, you grew to like wills. At first, he scared me. He scared me bad.

“”I always said if he ordered us to dribble off the Kalakala, we’d all be fighting for the first ball.””

Eathorne, like Soriano, learned his lessons well.

“”What wills showed me was that if you wanted to be good, there was no easy way to do it,”” Eathorne said. “”If you wanted to be a shooter, then go out there and shoot. You can’t dream it. Nowadays, I see so many players who are dreamers.””

The wild ones

Wills had a soft spot for kids like Eddie “”Bud”” Bilden, whose family, attracted by the prospect of work, moved here from North Dakota during the boom.

Bilden fell in with a rough crowd and ran away when he was 13, hopping a train to Montana and hitchhiking back to North Dakota. When he returned to Bremerton, he fell in and out of school. ken and Ta took him into their home on several occasions.

“”He called me Junior,”” Bilden said. “”I never had none of that before. Everybody else’s dad was always there if you played ball. My dad would never be around. He didn’t know how to show affection. ken was such a nice guy. When he talked to me, he knew how to make you feel like you were somebody.

“”I wish I would’ve listened to him a little bit longer.””

Wally Erwin, now 71, became embroiled in a mess that landed him in jail during his sophomore year. His father had abandoned the family, and he teetered on the fringe of an adolescent abyss before wills pulled him back.

“”I didn’t have much going for me,”” said Erwin, who earned 12 varsity letters in three sports at the College of Puget Sound (now UPS) and eventually received a master’s degree from the UW and returned to UPS to coach basketball and baseball. “”He changed my life, or I could’ve been a real bum. Easy.””

When graduated from Bremerton, Erwin received a perk wills reserved for special accomplishments: a night on the town in the coach’s sleek Buick.

Cinders and thinclads

If basketball remained his primary love, wills still accumulated a resumÈ studded with state track champions by 1941. Leo Brott won back-to-back titles in the half-mile in 1939-40. Jim Crump set a state record in winning the mile, and Jim Cummings took state in the quarter-mile.

“”He just took me under his wing after the Depression,”” said Brott, now 77. “”Other than that, I could’ve been nothing. He bought me track shoes and track pants. I didn’t have anything, and he bought me all the equipment so I could run.

“”Of course, I know why he done it. I was a pretty damn good runner.””

Ethics, humility, selflessness

Each year, the wills sent players Christmas postcards adorned with posed shots of themselves. Soriano’s scrapbook is lined with them, including one in which wills congratulates him on being among his best, “”if not the best.”” The coach included a gentle warning.

“”But never let on that you think you are superior,”” wills wrote. “”Good men are found out; they never have to impress others.””

Straight-laced, religiously competitive, moralistic, wills’ exhibited a selflessness beyond the normal range.

“”Everything he was trying to do for you was to better yourself. It was not for him; it was always for you,”” Soriano said.

“”A lot of people are going to condemn him because he wasn’t a full-bore Christian,”” Soriano said. “”But a lot of his thoughts, his ethics … there isn’t a religion I know that teaches it as well as he taught it.””