Thelma “TA” Wills, 93, lives on with the memories of husband, Ken Wills

By Terry Mosher

Editor, Sports Paper

It’s a splendid view from her lofty perch, the mirror-like waters of Sinclair Inlet shining back at her, Rich Passage off in the distance, across the water, on the far shore, trees waving in the light breeze, outside the house the lawn beautifully landscaped, the bloom on the flowers striking in their brilliance.

Yes, life is good even if the eyes don’t function as well as they once did when they were used to smash winning shots just inches off the baseline, even if a visitor has to inch close and speak loud to be heard. Even if the legs that took her on daily walks for over 50 years across the Manette Bridge, down Washington Avenue, and a right turn to the core of downtown Bremerton to check on her stocks and friends don’t work as well anymore. Yes, there is a lot to be thankful for as the days turn into nights, the nights into weeks, the weeks into months until August shows up and the calendar says Thelma (Dane) Wills is now 94, nearly 43 years removed from the day that still leaves a void and more unanswered questions than answers.

The shot rocked Bremerton on November 19, 1962, coming as it did so soon after the heart of Phil Pesco stopped as he sat at his home just yards away 15 days before.

Two of the best — maybe the two best — coaching minds in Bremerton basketball history gone just like that. One day, the sun is smiling, the cool November air feels good as it sweeps down on its captive residents ….. then Ken Wills follows Pesco onto the obit page and the world of basketball just doesn’t seem the same.

Ken Wills and wife Thelma “Ta” Wills —- two peas in a single pod. Pals, lovers and partners in everything. When Ken Wills wasn’t taping an ankle, holding open gym, teaching his young boys at Bremerton High School the fundamentals of basketball and life and coaching track and field, he was with Ta, and if you wanted to really catch up with them both, search the tennis courts.

“We did everything together,” Ta said, including being with Ken’s teams on their bus trips, hosting the athletes at her and Ken’s home, helping Ken help them out when they needed personal assistance.

Ta, a strikingly beautiful woman with a powerful athletic built, played as many sports, participated in as many athletic pursuits as allowed in those unenlightened days for young females.

They stopped holding the Kitsap County Tennis Championships at one time because the people who ran it got fed up with the same people winning the trophies year after year. What’s the use? they said.

Maybe if they had called it the Ta Wills Rule, you could have gotten angry. After all, it was Ta Wills who ruled the local tennis courts. If you wanted to win the mixed doubles championship, call Ta.

And they did. All of them.

“She won many county championships (8 years) and city championships in tennis,” says Louie Soriano, a name that often gets invoked when the talk turns to basketball. “I was fortunate enough to play with her a couple times when we won county championships.

“It was a big thing back then. This is a small community and Thelma would pick somebody out to play mixed doubles and they would win.”

Of course, Ta also won all the women singles titles. And when there weren’t any fellow ladies around to beat on, she would beat the men.

“I just loved to play since the time I was a freshman in high school,” says Ta. “I brought a racquet for 98 cents at the drugstore. It’s all you could afford.

“I lived out in the country and I would dribble the ball with the racquet all the way on the old logging alley on the way going home (from school). I just loved to play. I loved to play everything anyway, track, basketball, tennis.”

Thelma Dane was born August 20, 1911. If it had been known what kind of person she would become, maybe God would have speeded up the process and given her to the community sooner.

But August 20, 1911 it was.

“I was the first white person born at Kitsap Lake,” says Ta proudly. “It was all Indians (Native Americans) before then.”

Ta is Bremerton through and through. Bremerton born, a Bremerton High school graduate (1929), school secretary to the principal, superintendent and to the principal of evening school until 1938, married to a Bremerton High School coach, office manager at the Schutt Clinic for 30 years in downtown Bremerton, she could never think of living anywhere else.

She just never thought it would be so long living in Bremerton without her closest friend, her best pal, her first and only love.

“I never went on dates. Ken never went with girls,” Ta said. “He said he only (dated) one girl (at Washington State) and he saw her kissing some guy behind the barn so he never looked at another girl after that.”

Their first date was supposed to be to a Hi-Y (school club) Banquet, but Ken got back late from the gym, so he said, “How about going to the show?” Ta said. “He must have mentioned it to the kids (his players) because when we got to the show, two rows of kids sat behind us.”

The name of the movie?

“3 Smart Girls,” said Ta, who exchanged wedding vows with Ken June 13, 1939.

Ta lives on with the memories, and all the stuff they accumulated together. All the yearbooks, the clippings, the photos. The mail box still says Ken Wills. The phone listing is the same as it was on that terrible November day in 1962.

The memories include the death of Pesco, who died of a heart attack on Nov. 4, 1962 at age 54, at his home next to the Wills home in Bremerton.

“He died on a Sunday afternoon,” Ta said, “sitting on the davenport. Just dropped dead. Mary (his wife) came over and got us right away. But he was already gone.”

Pesco was the athletic director and basketball coach at Olympic College when he died. Wills had recommended his former Washington State basketball teammate and friend for the job.

Wills and Pesco were the Odd Couple. Wills, ever the perfectionist, and Pesco who carried gravy strains on his shirt. But together they were the heart and soul of basketball in this area, and in the state.

Pesco won six junior college championships in 14 years at OC and three straight years took the Rangers to the National JC Tournament in Hutchinson, Kan. His 1949 team went 32-2 and finished fourth at Hutchinson.

He was inducted into the Northwest Athletic Association of Community Colleges Roll of Honor in 1989 and the MVP of the annual men’s NWAACC Basketball Tournament is named after him.

But late in 1962 while Art Morken was in the process of getting elected for the first time as Kitsap County Sheriff, Pesco slumped over at his house to set into motion a chain of events that 15 days later would end with the 51-year-old Wills pulling the trigger on a gun he’d brought at Bremerton Sport Shop just a few hours before, sending a .38 caliber bullet into his head and sending ripples through the air surrounding Kitsap County that still reverberate to this day.

Ta’s best pal was gone.

What was, was. So Ta has continued on, but there isn’t a day that she doesn’t think of him. His presence in the house they shared after they purchased it in 1948 is still very large in her mind and in physical reminders.

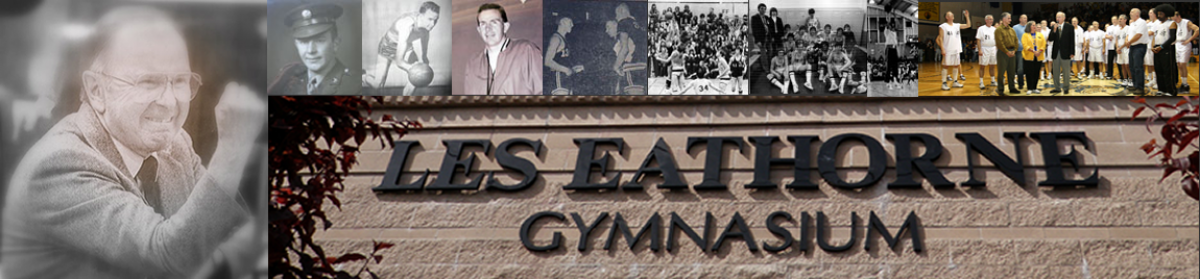

When Pesco died, the pressure had built on Wills to replace his friend at OC. Pesco’s players wanted assistant Roy Critser, OC football coach Don Cooley was a conditional candidate and Wills, Critser and Les Eathorne, then coach at East High School in Bremerton, all submitted applications.

Poulsbo’s finest, Harland Svare was being named the Los Angeles Rams replacement head coach for Bob Waterfield about the time the school board in Bremerton gave the job on November 16, 1962 to Wills, the reluctant applicant who loved his job at Bremerton High School and dreaded coaching at OC, which was not near the job at the time that the job at the high school was.

Ta said there had been some pressure within the high school administration, especially from principal Fred Graham, to move Wills on because he had become bigger than life and jealousy began to crack the fabric of school unity.

“Graham told Ken he’d fire him in two minutes if he had his way,” Ta said. “The administration and school board’s way to solve a problem was to send them to the college and make it seem like a promotion. To Ken, it was a demotion.”

So the deed was done.

Thus began the tick-tick of the clock in the finals hours of Wills’ life.

“He put me on a pedestal and said he would never do anything to humiliate me,” Ta said. “He said if he ever did, he’d shoot himself. He thought he was being humiliated by being forced to go to the college.

“And he had this black players petition against him (at the college). There was a rumor going around that Ken would never use colored kids. In track and in basketball, Ken had colored kids. But you know how rumors are.

“So Ken went down to Florrie Swan’s (Bremerton Sport Shop) and brought this gun. He told Florrie he needed it for me so I could protect myself when he was gone.

“He paid for it out of petty cash he had. In the note he left he said he left the bill for the gun and I could take the gun back and get the money back.”

Wills played for Walla Walla High School in the state basketball tournament in 1928 and 29, played three years on the varsity at Washington State.

While a Walla Walla student, Wills spent countless hours in the gym. During the summer, he was out picking fruit to make money and on the way back with the truck late at night he couldn’t wait to get within the sight-line of the gym to see if the light was still on so he could go play.

“His heart would just pump when he’d see that the light was still on,” Ta said. “He just loved it. He liked the smell of the ball.”

Once Wills landed in Bremerton, he started his climb into basketball lore, earning what should have been state Hall of Fame honors (his sudden death ended that) while building a program that was feared from one end of the state to the other.

His 1941 basketball team with Eathorne a junior won the state title. The next year and in 1946 and 48 his teams took second at state. From 1940 to 1959, Wills had Bremerton in the state tournament 15 times, ten times finishing in the top eight, including a third in 1952. He had all-staters like Eathorne, Alan Maul, Ted Tappe, Al Murphy, Howard Thoemke. And Ron Patnoe went on to coach Seattle’s Garfield to the state title.

During World War II when some of his former players were scattered around the world, reports would come back that others wondered how these Bremerton players got so good at basketball.

Their answer?

Wills.

Wills, who just missed making the U.S. National Team in the 1500 at the 1932 Olympics (he lost by 3-tenths of a second to Glenn Cunningham in a three-way race-off to make the team; Cunningham went on finish fourth in the 1500 at the Games, held in Los Angeles), built his basketball teams on fundamentals, insisting that his players be solid or sit. Along the way he built relationships that have endured long, long after the shot. Those still living remember Wills as if it was yesterday he was blowing the whistle at them in the Bremerton gym.

And Ta remembers, too.

“Ken didn’t play much tennis at first. He fiddled with it,” Ta said. “He said that men can always beat women because they have more muscular stature.

“It took him 13 years for him to be able to beat me consistently.”

Tennis was such a part of their life, that Ken and Ta built their own tennis court.

“We built a tennis court instead of a house, in fact, at the end of the football field at the high school, 17th and Ohio,” Ta said. “We bought the lot so maybe we could build a double-story house and just watch all the games from the house.

“Every spare minute we had we’d run up to the tennis court. We’d carry gunny sacks in the back of the car and if it rained and there were puddles on the tennis court, Ken would wipe up the puddles so we could play.”

After Ken died, Ta did well in the stock market (especially on Telmex and Microsoft) and helped others make money as well.

“She’s been an inspiration to people over the years, and I’m not just talking athletics but her optimism about life,” says Larry Tuke, who is her stock broker at Smith Barney.

“For years, when we were Foster Marshall in downtown Bremerton, she’d walk to our office every day. She knew more about the stock market than myself or anybody who worked for me down there.

“She really understands the stock market. There were people who came to her for advice about the stock market, and she would send them to me. Most of the time she was right. There were people who made hundreds of thousands of dollars based on her recommendation.”

The Bremerton gym was packed when Bob Bryan, one of Ken’s former players, delivered the Ken Wills eulogythat sad November day.

John K. Smith’s story in the Bremerton Sun summed up Ken Wills, the perfectionist.

“He took the job he did not want. He believed he could not do the job perfectly,” Smith wrote. “(But) he would do not less. He could not refuse the job. Ken Wills, nor any Ken Wills team, ever quit.

“The strength that makes a man great,” Smith finished, “may be the weakness that can’t be overcome.”

The days go quietly these days for Ta Wills. Surrounded by the city she loves, the water flowing by her in peaceful harmony with the trees lining the shores, content in the knowledge that the only man she loved, loved her too.

“Sure I miss him, but not much I can do about it,” says Ta. “I just always say I’m married for ever and ever and ever.”